Perry's Saints

or

The Fighting Parson's Regiment

• Title

• Author

• Preface

• Chapter I

• Chapter II

• Chapter III

• Chapter IV

• Chapter V

• Chapter VI

• Chapter VII

• Chapter VIII

• Chapter IX

• Chapter X

• Chapter XI

• Chapter XII

• Chapter XIII

• Chapter XIV

• Chapter XV

• Chapter XVI

• Chapter XVII

• Chapter XVIII

• Chapter XIX

• Chapter XX

PERRY'S SAINTS.

CHAPTER XIV.

Bermuda Hundred. Compauy E as skirmishers. Battle of Chester Heights. Couldn't resist the temptation. Company E fighting on its own account. Bad predicament. Company E did nobly. More fighting. In sight of Richmond. Confederate sharpshooters cleaned out. Battle of Drury's Bluff. Company E again in a bad spot. Wonderful examples of discipline and soldierly conduct. General Terry to the rescue. Retreat. Back to old quarters. Captain Lockwood.

[May, 1864]

MAY 3 and 4 the regiment did picket duty, and on the 5th left on the steamer Delaware, and sailed down to Fortress Monroe, up the James River, past City Point, to Bermuda Hundred. On the 6th we landed, and, after a brief delay, marched several miles up the Bermuda Hundred road. Early on the morning of the 7th we started again, and, after marching and countermarching for several hours, approached Chester Heights. Behind the hills which concealed us from the enemy, we left our knapsacks, blankets, and other impediments, and the order to advance was received, when we resumed our march, with 205 Company E thrown out as skirmishers. The instructions received by me from the colonel were general, and somewhat indefinite, the only point well understood being that we were to clear the front of any opposing force. Grasping this idea and at the same time our muskets, we worked our way forward through the woods, until we found ourselves on the top of a hill, with the whole Confederate force in view in the valleys below. But we were entirely separated from our regiment. After vainly endeavoring to take up the connection, we were finally compelled tQ the conclusion that if we were to have any further part in the affair, it must be by acting independently. Before us, in the vast amphitheatre, so completely enclosed by the surrounding hills that there seemed no avenue of escape, was the enemy, against whom our attack was directed. Every movement was plainly visible, for not a tree or stone obstructed our view. The utmost activity prevailed, and officers were observed hurrying to and fro, while the changes that followed showed that every preparation would be P1ade to repel attack. One officer, especially, who seemed to be in command, was conspicuous, as he rode about on his white horse, and our men amused themselves for some time in vain attempts to reach him with their rifles, but he was too far away.As the scene comes back after the lapse of so many years, it seems impossible that the picture imprinted upon the memory can be that of war. That deep, quiet valley, the rich green of its meadows, the protecting hills which circled it, the little hamlets which told their stories of homes, of comfort, and happiness, constituted a picture so peaceful and restful, that those bodies of armed' men whose movements we were watching, and the bristling cannon and flashing muskets, seemed strangely out of place.

But there was little time for contemplation. The batteries, one after another, sped up the hill, and, lost for a time, reappeared again, and took position far off to our right, giving us the first intimation of the position of our own troops. Following the same general direction, the several battalions moved up to the support of the batteries, or took positions on the sides of the hills, where they could most effectually resist the advance of our troops. Some two or three of these battalions lay down near the railroad which ran around the valley at the foot of the hills, to be out of the way of our fire, and at the same time be ready to engage in the action if required. These offered altogether too tempting an opportunity to be resisted, and, rushing down to the turnpike, which at this point ran parallel to and very near the railroad, we opened on them a terribly galling and destructive fire. It was a sad predicament, for they could neither return our fire, nor change their position, without exposing themselves to the fire of our main line. When, however, this wavered and fell back1they were at liberty to devote themselves to us, and, with a yell of rage, they precipitated themselves into the deep cut of the railroad, and for a few moments the whistle of bullets about our ears was like the hum of angry bees, whose hive had been disturbed. A large number of Company E of the 7th Connecticut regiment had been doing good work, but with no officer to command them. These joined with our men, and, by carefully availing themselves of such shelter as offered, both companies were brought out of the fiery shower with but slight loss.

Proclamations from headquarters announced the complete success of this expedition, but those who participated in it were unable to discover the success. The whole Confederate force should have been captured, for, once driven into the valley, there could have been no escape for them. Only one division of our corps was engaged, and that not seriously. A portion of the railroad and telegraph line was destroyed, causing a temporary interruption of communication between Richmond and Petersburg. The losses on both sides were small. Dunn, orderly sergeant of Company E, deserves special mention for his coolness and bravery, but every member of Company E is to be commended. Although dreadfully exposed for a few moments, they obeyed orders as if on parade, and it is to their prompt obedience and strict discipline they may impute their safe conduct out of their perilous position. The material of the company was of the best, and it had been specially favored in having such commanders as Coan and Lockwood. Had Sergeant Dunn showed less soldierly pride (which, however, was very noble in him), he would have avoided the painful wound from which he suffered so long.

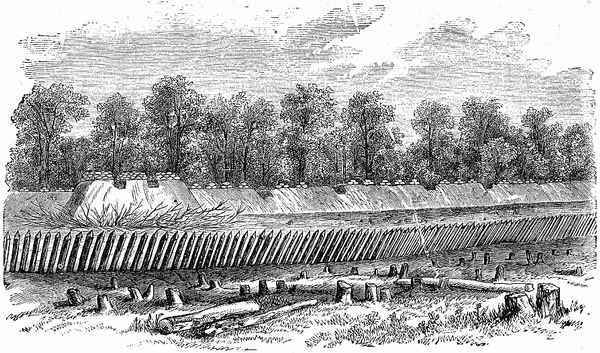

On the 8th, we rested; on the 9th, we fought with what were generally called in our camp I Gilmore's rifles. In other words, we worlfed on the intrenchments with picks and spades, and occupied the intrenchments at night. The firing was heavy all about us, and it was rumored that Butler would be able to enter Petersburg in the morning. On the 10th, we shouldered the Gilmore rifles again, but at ten o'clock in the forenoon wer'e ordered to the front, to support Colonel Howell, who was reported falling back; were exposed during the day to the fire of the enemy, but were in much more danger from the fire in the woods, which were burned to clear them from Confederate sharpshooters. Quite an engagement occurred in our front, in which our batteries did fearful execution. General Foster, who went out on flag of truce, reported seeing heaps of Confederate dead in the edge of the woods, many of them half-burned. General Butler did not

LINE OF DEFENCE AT BERMUDA HUNDRED.

enter Petersburg, being deterred from making any forward movement by the battle in his rear (so it was said).

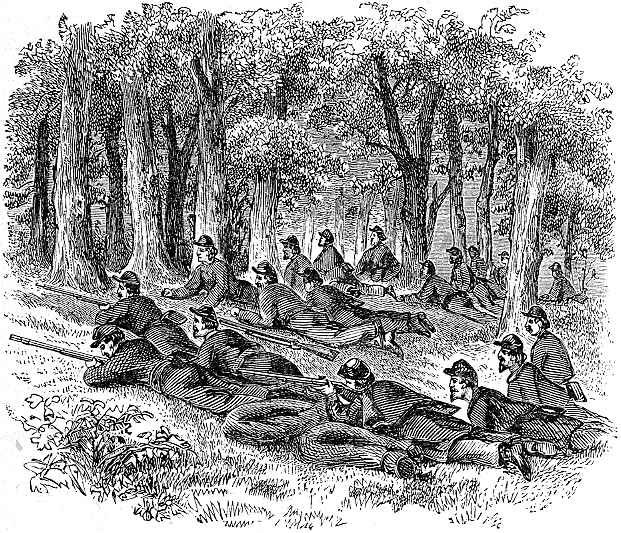

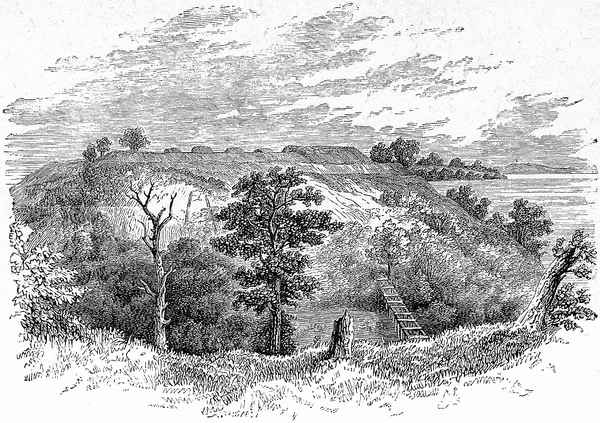

On the 11th, we rested, and early in the morning of the 12th started away from our intrenchments at Bermuda Hundred, and marched all day in the rain. Rested at night as best we could, with no shelter but the dripping trees (for the rain continued through the night). On the afternoon of the 13th, we moved forward and up to the turnpike, about two miles, where from the tops of the trees those so inclined obtained a view of Richmond and Fort Darling.. Again on the 14th, we moved forward into the advance to relieve the 76th Pennsylvania regiment, having up to this time acted as reserve. Our position was about in the centre of the main line, with our right near the Richmond turnpike. Generals Terry and Ames were on the left, and steadily moving forward. That night we occupied the old lines of the Confederates, from which they had been driven by General Gilmore. The 15th was a trying day, for the most of the regiment were out on picket duty, or skirmishing through the woods in our front. The firing of the Confederate sharpshooters, many of. whom were stationed in trees, was very annoying, until Our men, becoming desperate, hunted them from

PICKETS ON DUTY.

their places of concealment, and before night that mode of warfare was effectually stopped. No quarter was given, and no mercy shown. Still, the firing from the rifle-pits was kept up without intermission, and quite a number of our men were wounded. Very early on the morning of the 16th, we were conscious that something serious was impending. The irregular firing of musketry was first heard on the extreme right; this was soon followed by regular volleys, mingled with the roar of artillery, and as it continually approached, we knew that it meant a serious disaster to our troops; we could feel the conflict rolling up against us, and quickly disposed our men along the irregular and broken line of wall and fence. Unfortunately, no attempt had been made to construct a regular line of intrenchments, and there was little protection for our troops. About 8 o'clock in the morning, the regiment on our right gave way, and left our flank exposed, and the Confederates poured in upon us in overwhelming numbers, but the brave men of Company E, who held the right of the line, would not give way, but stood their ground as firmly as if no danger threatened, while the Confederates surged in upon them in such masses that it seemed impossible that a single man could escape. The position which they occupied was somewhat in advance of the remainder of the regiment, on a little natural terrace, so that it was some time before the commanding officer was aware of the critical situation in which we were placed, and the order to retire was not received until that little kHoll was literally covered with the dead and dying. Corporals Smalls and Brassell, and poor Jockers, the brave little man from the Enfans IPerdus, with eleven others, lay dead or wounded, while others, less severely injured, had made their way to the rear.

In the very hottest of the fire, Lawson, the orderly sergeant of the company, hobbled up to where I was stationed, and, saluting, said, "I am wounded, sir." "Go to the rear" was the reply. A ball had passed completely through his thigh. Corporal Burton; almost for the first time in battle, having, for the most part, been employed as a clerk at division or corps headquarters, came to me, and, saluting, exhibited his wound, while every line of his countenance told the anguish he was suffering. A ball had shattered his hand while he was in the act of loading; but he would not go to the rear without the order of his commanding officer. Never shall I forget the brave soldier Vreeland,

FORT DARLING.

who, stationed behind the little apple-tree, continued loading and firing, until fairly dragged away, so grievously wounded that there was no hope of recovery. As I write, I feel that every name in that heroic band, the living and the dead, should be inscribed in letters of gold on the pages of history. Such faithfulness, such heroism, such discipline, I never saw exhibited elsewhere. Better soldiers never lived; braver men never died. Not a man left that knoll without permission till the order came to retreat. But what confusion followed! Who of those present will not recall that struggling mass of broken regiments; hopeless, and distracted, until the cool self-possession of General Terry brought order out of the confusion, and led the way out to safety and security. N at a moment too soon, for as we toiled our weary way up the hillside, the shot and shell from the Confederate batteries in the turnpike made many avenues through the retreating columns. And very glad were we when the distance and intervening hills secured us from further annoyance.

We should here state that the right of the line, which was the first to give way before the Confederate assault, was under the command of General Wright; while the left of the line, under General Terry, resisted every attack, and only retreated when the danger of being cut off and captured became imminent. That night we spent in our old camp, near the intrenchments at Bermuda Hundred; and the following day rested. On the 18th, did some picket and skirmish duty, and on the 19th were still in the front, enjoying the music of shot and shell; and to the 28th, there was little rest, night or day, between fatigue, picket, and skirmish duty. The enemy made frequent attacks on our outer lines, but without success; and we could observe them for the most of the time engaged in constructing intrenchments. General Butler was not accomplishing the work allotted to him. Petersburg was not taken, and no important advantage had been gained.

On the 25th, Captain Lockwood left us, to return to civil life. It was a great

loss to the regiment, for he was a good officer, an intelligent man, an

agreeable companion, and a loyal

friend. The places of the old officers, so many of whom have fallen in battle or

have voluntarily left the service, cannot be fined.

They were royal men, who were borne into the service by that first fresh, pure

wave of patriotism which swept over the North in the earliest days of the war.

Of them all, Lockwood was my most intimate friend - respected, trusted, and

beloved. Returning home, he engaged in the business of manufacturing, in 'which

he continued until his death, which occurred some years after the war. closed.

He and Lieutenant-Colonel Strickland were law partners in New York city at the

breaking-out of the war.