Perry's Saints

or

The Fighting Parson's Regiment

• Title

• Author

• Preface

• Chapter I

• Chapter II

• Chapter III

• Chapter IV

• Chapter V

• Chapter VI

• Chapter VII

• Chapter VIII

• Chapter IX

• Chapter X

• Chapter XI

• Chapter XII

• Chapter XIII

• Chapter XIV

• Chapter XV

• Chapter XVI

• Chapter XVII

• Chapter XVIII

• Chapter XIX

• Chapter XX

PERRY'S SAINTS.

CHAPTER V.

Expedition to Port Royal Ferry. Progress up Broad River. Colouel Perry acting brigadier-general. The rebel yell heard for the first time. The regiment's first baptism of fire. The old horse. Night on the field. Return to Hilton Head. Object of the expedition. Presentation of flag to the regiment. Off for Dawfuskie. Southern homes. Preparatory work by Major Beard and others. Building batteries on Jones and Bird Islands. Mud and malaria. Reconnoissances and midnight wanderings.[January 1862]

THE closing day of the year brought rumors of a contemplated movement. The scene of operations, and their extent, were only subjects for conjecture. Early on the last day of the year, we received notice to be in readiness to march with a number of days' cooked rations, and about noon of that day sta_rted for the dock. The expedition was under the command of General Stephens, and two regiments were taken from our brigade,- the 47th and our own,-in addition to those of his regular command. By the middle of the afternoon we were on board of the steam transport Delaware, and on our way up Broad River towards Beau- fort, where we anchored for the night. In the early morning, we started for Port Royal Ferry, against which point we learned that the expedition was directed. Several gunboats accompanied us, under the command of Captain Rodgers. Our progress up the river was slow and cautious, until we arrived opposite the plantation of Mr. Adams, where we disembarked.We were much interested, while on the steamer, in watching that portion of our troops already landed, as they could be distinctly seen, pursuing their winding way through the woods and over the fields, their bayonets glistening in the sunlight. Sometimes they went at. slow step, at others in quick or double-quick time. Sometimes they fired, and charged the Confederates whom they encountered, while the gunboats covered them to guard against attack by superior forces, all the time shelling the woods in front of them as they advanced. As soon as landed, we formed in line and moved forward, the two regiments-the 47th New York and our own - under the command of Colonel Perry. Acting as "reserves, the duty assigned us was to intercept the Confederate retreat. Very soon, however, orders were received to. attack the battery which was found to cover the road over which we were expected to advance, and the 47th was moved through the woods on the right to attack it in flank, while the 48th was to charge in front. Some delay occurred in establishing the position of the 47th, and ar. ranging so that the attack might be simultaneous. Well do I remember the rebel yell, heard for the first time as I was returning from conveying orders from our colonel to the 47th. Accompanied by the discharge of cannon and musketry, it seemed, to my unaccustomed ears, as if the inhabitants of pandemonium had been let loose, and as I rounded the last point of woods which shut out ftom view the scene of operations, I expected nothing less than a handto-hand conflict. Instead, I found the regiment lying quietly down between the furrows of a cornfield, over which the Confederate shot skipped harmlessly. In this way the men were protected while awaiting the final order to charge. This was found unnecessary, for the yell of the Confederates proved only the parting ,word given while in the act of abandoning the battery, which was speedily occupied by Our troops. The guns were removed, and the works destroyed, and we continued our advance towards Port Royal Ferry, where the enemy was known to be strongly entrenched.

At this time two horses had been captured and placed at the disposal of the colonel and his aid, to which position I had been appointed. I have no recollections of the colonel's, but my horse soon gave evidence of manifold infirmities. Three times we rolled over together on that cotton-field, before it was discovered that, with his other weaknesses, he was stone blind, when he was left to tempt some other officer, and I returned to nature's conveyance, sadder and sorer for the experience. That night we lay down on the field, but gained little rest, as the Confederates were known to be in force in the vicinity, and an attack was looked for. The next morning we embarked for Hilton Head, the objects of the expedition having been accomplished, in the destruction of the Confederate works, which were being constructed for the purpose of preventing any forward movement on our part in that direction, and confining us closely within the territory. already captured. This was only one of the points which the Confederates proposed to fortify, which were intended not only as a restraint lJpon any forward movement by us, but also as bases of aggressive operations against us.

January 12 the regiment was presented, through Adjutant Goodell, with a beautiful flag from the ladies of Hanson Place MethodistEpiscopal Church of Brooklyn, of which Colonel Perry had been pastor. That flag has waved over many battle-fields, and is a witness that the 48th never faltered in the discharge of any duty. It is now In the custody of the Long Island Historical Society, having been committed to its charge, with suitable ceremonies, on the evening of April 21, 1881.

January 25, 1862, we broke camp, and marched to Seabrook's Landing, on our way to Dawfuskie, an island bordering .on the Savannah River, some four or five miles above Fort Pulaski. That night we spent at Seabrook's, and on the next morning embarked on the steamer Winfield Scott, and proceeded to a place on Dawfuskie called Hay's Point, where five companies disembarked, and at 9 P. M., under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel Bar. ton, started for the other side of the island. Three hours of wearisome marching brought us to Dunn's plantation on the bank of the river. Pickets were established, and sentries posted, and we got what sleep we could. The next day was occupied largely in procuring supplies of food, as everything of that nature had been left on the Winfield Scott. Detachments were sent out in all directions to secure the cattle, pigs and poultry abandoned by their owners 011 the approach of our troops, and to collect whatever else could be found that was edible. The men were quartered in the houses and sheds, while the officers occupied the family mansion. In the afternoon we learned that the Winfield Scott had been wrecked on Long Pine Island, where the other wing of the regiment remained until taken off by the steamer Mayflower, which conveyed them, with the regimental baggage and supplies, to Cooper's Landing, on Dawfuskie. At this point they remained until February 1, when they joined us, and a permanent camp was established near the borders of the woods, a little way back from the river.

During the interval there was little of severe duty, and all were allowed the largest liberty consistent with proper discipline. Frequent excursions were made to different points on the island, especially to the beautiful residences along the shore. Of these, the most attractive were Munger's and Stoddard's, the former a short distance below us, the latter some miles away, and occupying a commanding position, overlooking the sound. Both gave evidence of large wealth and cultivated tastes, in the character of the houses and beauty of their surroundings, and as we wandered through the shaded avenues, and among the shrubs and flowers, in gardens where roses and japonicas. grew in tropical luxuriance, where the air was full of sweet odors, and the eye confused with the multitude and variety of brilliant colors, and remembered that these abodes of happiness and beauty had been abandoned to pillage and destruction, and that wherever our armies penetrated, homes would be broken up, and in the place of comf6rt would come suffering, and in

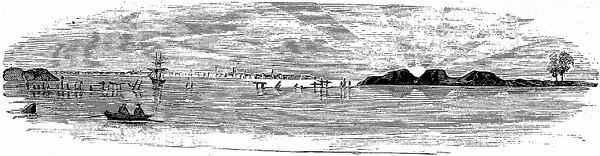

OBSTRUCTIONS IN SAVANNAH RIVER.

the place of beauty. desolation, we cursed the madness of those who had brought such miseries on the land.

While we were enjoying this short season of comparative idleness, active and aggressive operations were going on all about us. Expeditions were planned, obstructions removed from the creeks and rivers where openings were. desired, and midnight scouting parties penetrated the surrounding country in all directions, even to the very walls of Pulaski. In all of these, Major Beard, of our regiment, took a leading part, and did most efficient service. As we sat around the fire one evening at Dunn's, he sud- denly appeared among us, with General Gilmore, who had already been promoted from the position of Captain of Engineers in the regular army. to that of Brigadier-General of volunteers. They had just returned from the work of clearing the spiles from Wall's Cut, by which a convenient way was opened for our boats to the Savannah. Much of the night was spent in listening to their adventures, but we little knew how intimately connected these were with our own immediate future.

It was not long after our camp was established, before we had our full share of labor and danger. It had been determined to establish batteries on the islands of the Savannah, to cut off communication with Fort Pulaski, and prevent re-enforcements and supplies. The points where these were to be located having been selected, the engineers were ordered to prepare the materials for their construction, and our regiment and a portion of the 7th Connecticut were employed for weeks in conveying this material from the wAods to the dock for transportation. Some eight or ten thousand logs,

[February 1862]

of from ten to fifteen feet in length, and from three to six inches in diameter, were carried a distance of from three-quarters of a mile to a mile and a hal-f, on the shoulders of our men, and, in consequence, many of our best soldiers were ruptured or otherwise injured, and crept out of the service, maimed and ruined for life. Late on the evening of February 9, a detachment under Captain Greene was ordered to report at the dock to complete the loading of the Mayflower. It was raining very hard, but the men worked faithfully until after midnight, when word came from brigade headquarters to take off a part of the load. This was done, and the admirable foresight of the commanding general was fully appreciated, as was manifest from the frequent comments in which the men indulged, which had the merit of earnestness if not of elegance.At 3 A.M. of the 10th, we started for Jones Island. We were all wet, hungry, and tired. Not expecting to leave Dawfuskie, we had taken no provisions. There was no opportunity for sleep, for, arriving quickly at the point of debarkation, the work of unloading and conveying the materials across the island was pushed forward hurriedly. It was a season of the year when, even in this southern latitude, the sun gave but scanty heat, and the men must needs work lively to keep the blood from chilling. The island was but a deposit of soft mud, into which they sank to their knees at almost every step, while occasionally the logs or planks which they carried were needed to bridge over spots otherwise impassable. During the. forenoon, a party was despatched to camp in a small boat, for food, but the. supply which they brought was totally inadequate, from the size of the boat and the number to be fed. During the day all the materials for building the battery were conveyed across the island, a distance of about a mile.

While engaged in this work, a Confederate steamer made its appearance, and stopped opposite, and so near to us that every movement of those on deck was discernible. The officers, with their glasses, scoured every point in the vicinity, while we crouched down among the cane-brakes. So long as the steamer remained, we expected a shot from her guns, or a closer inspection by one of her boats, which would have been extremely disagreeable, as the order for detail required us to leave our guns in camp, and there were not six rifles on the island. Fortunately we were not discovered, and the steamer, after a little delay, proceeded down to Fort Pulaski. About this time the guns for the battery arriv,ed, and the general in command of the district, who had arrived with them, declared that they must be mounted before morning. We felt very much like harnessing him to the foremost, and giving him a taste of Jones Island mud, but there were objections to such a procedure, and, instead, we made a platform on which to load them, and prepared to do our utmost. By frequent crossing and recrossing, a way had been sufficiently marked through the canes, but the constant tread of heavy feet had reduced the soft mud to the consistency of oil for a depth of several inches, making a road not perfectly calculated for the transportation of cannon. However, there was no time for hesitation, and placing two planks before the wheels, we united our strength in the task of maintaining them on these planks, while we carefully urged them on, replacing the planks as we proceeded. Woe be it, if, slipping on the greasy mud which covered the planks, as they sometimes did, they buried themselves in the soft embrace of its slimy nastiness. Should it be asked how were they recovered, it would be impossible to tell. We can only say they were, and that with slow and suffering steps we guided, pushed, and pulled them forward, until flesh and blood rebelled at loss of food and sleep, and they were covered up, and we ordered back to camp, to be relieved by others. We had to wait, however, until the relief came from Dawfuskie, and I quote from Sergeant Thompson's journal to show how this second night was spent: "At midnight we covered the guns and endeavored to find some place to lie down in. Found a place, but was soon routed out by the tide. Came to the conclusion to walk the rest of the night to keep warm. Found a twenty-foot plank with four men on it! Jumped on and ran my chance. Kept moving until morning." This was only the beginning of such labor and exposure, and is it a wonder that so many men, protected from rebel bullets, have come out- of such a service as we have here described, to worry through a life of suffering, the effects of which they have transmitted, and will continue to transmit to children and to children's children. The malaria of those mud islands is considered death to anyone, even to such as have been acclimated to the South, and their only inhabitant is the ugly alligator.

This battery was hardly established before, pushing across the river, another was planted on Bird Island, farther up, so that, together, - they - cut off all further communication with Fort Pulaski, by way of the Savannah. An attempt was made to destroy these batteries, but without result, except in the disabling of several of the enemy's steamers, after which we were left in undisputed possession.

The smell of the mud of Bird Island lingers in the nostrils yet, and it is no wonder that in the progress of the work of establishing the battery, at times not a man was fit for duty. Whiskey and quinine were powerless to stay the effects of such labor and exposure. As a partial protection, our tents were nailed to heavy timbers a foot or more in diameter, snatched from the river as they floated down, while boards were laid across on which we slept, but even then in the high spring tides we were scarcely out of water, and not a spot was dry on the whole island.

During our stay on Bird Island, frequent reconnaissances were made up the river in different directions. One dark night, two boats were sent up the Savannah, on either side of Elba Island, to ascertain if batteries were being planted, which would threaten ours of Bird and Jones Islands. Closely hugging the s,hore, we worked along cautiously, to avoid being seen by the Confederate pickets. At a distance of some miles from where we started, while the pickets on the shore were plainly visible by the light of their camp fires, one of our men was attacked with a sudden and most sonorous cough. Suspecting that it was intended to stop our further progress, we waited patiently for its cessafron, and resumed our progress up the river, until suddenly the sound of voices immediately in front of us gave warning that we had gone too far for safety. Fortunately, the , tide had turned, and a single whisper stopped the motion of the oars, otherwise we should not have suffered long from the chillness of the night air. Dropping back with the tide, stopping occasionally to learn more certainly that there were no batteries where they had been suspected, we reached our quarters in season for an early breakfast.

Lying alongside, but extending much farther up the river than Bird, was

McQueen's Island, the upper extremity of which'was bounded by St. Augustine's

Creek, which connected the Savannah with Wilmington River, and afforded a

channel of communication with Fort Pulaski by means of small boats. Across St.

Augustine's Creek, the telegraph wire connecting the city with the fort had been

stretched on tall, heavily constructed spindles. The wire had been destroyed

some time before, but the fact that steamboats from Savannah, at some risk from

our battery, continued to come down to this point, and seemed busily engaged in

some

operations near these spindles, determined Major Beard, who commanded on the

island, to investigate the matter, and, if possible, to bring away a scow which

was known to be lying in that vicinity. The investigation was very proper, but

the object of getting the scow we never understood. However, a detail was made,

a boat was dragged across McQueen's Island to Wilmington River, and from that

point a small party, with a guide supposed to be acquainted with the region,

started for these spindles. It was a curious experience, paddling along under

the overhanging banks in perfect silence, save when the vivid imagination of

some one of the party pictured a Confederate picket from some peculiar

conformation of the shore or eccentric growth of bush or shrub, when a word of

caution would stay our progress until cooler eyes discovered the deception.

One of the party even descried a picket beside its camp fire, whose bright glow

shed a clear light upon their waiting figures, but to all the others there was

butt1jhe blackness of darkness, and we passed on without molestation. The leaky

little dug-out, which required constant

bailing to keep it afloat, had room for neither rest nor comfort. Hour after

hour we paddled along with the incoming tide, vainly hoping to reach the point

we sought, every moment taking us farther within the lines of the enemy, and

when, at last, completely lost amidst a maze of devious, winding creeks, the

tide turned, we turned also, and by marvellous good fortune found our way back

before the morning dawn discovered us to the Confederates. Determined to have

that scow, and equally determined to haTe a better knowledge of the country

before a second attempt was made, a small party was started one bright

afternoon, which, rowing some distance up the river, landed on McQueen"s Island,

and striking through the canes, made straight for the spindles. We took no

notice of the picket on the other side of the island, but kept right on, until,

approa.ching the shore of the creek, the men were held back behind the trees and

bushes which grew along the bank, until we could be assured of no special

danger. Satisfied on this point, they were a.llowed to come on, and we gathered

along the shore, and endeavored to impress upon each

others' minds the direction of the creek, the location of the scow, and the

probable means of reaching it from Wilmington River. The order to return had been

given, when suddenly the Confederates appeared from behind the timbers of the

spindles opposite, and not a hundred yards distant, and from the bushes near,

and the order to lie down was given none too quickly to avoid the bullets which

came whistling over our heads in close proximity.

No one of our party was hurt, and we never received an official report of the

number killed and wounded by our return fire. The locality was not sufficiently

attractive to induce us to remain until the report was made up. Not only the

danger of being cut off by the picket we had passed, but the shells from our own

battery soon began to trouble us, for, as it afterwards transpired, one of our

number, unaccustomed to the sound of bullets, became so thoroughly frightened

the first discharge that he started for camp by the most direct course, and on

his arrival announced that we had been attacked by greatly superior numbers, and

that he had been sent back for re-enforcements. Our

own battery was soon throwing shot and shell over our heads, much to our

discomfort, --for those missiles often make serious mistakes, and fall where

they are least intended, --and an that could be spared were preparing to set out

to rescue us from the peril to which we were exposed, when our appearance on the

river put an end to the alarm. On reaching the island, we found the utmost

excitement prevailing, and that every preparation had been made for the

reception and care of our wounded. The author of all this confusion was

discovered to b.e suffering the extreme effects of fright, and in a pitiable

condition of mental and physical prostration. His youth, for he was a mere boy,

shielded him from the consequences of his conduct, which otherwise would have

been very serious. He was never permitted, however, to forget the circumstances

and effects of his fright. Soon after this I was sent to Wilmington River to

intercept the despatch boats, which, we had reason to suppose, found their way

to the fort, but although many nights were spent in watching, while the miasma

from the swamps was doing its deadly work, penetrating to the

very bone and marrow, and preparing many a poor fellow for his final rest, the

creeks and rivers which intersected the country in all directions afforded

abundant means for avoiding us, and we made no captures.